- 1 Why You Should Care About This Plant

- 2 What Traditional Cultures Already Know

- 3 The Science That Backs It Up

- 4 Why It Works (And Why We’ve Ignored It)

- 5 How It’s Actually Used

- 6 The Modern Twist

- 7 What We’re Really Talking About Here

- 8 The Questions You Should Be Asking

- 9 What You Can Actually Do

- 10 The Bigger Picture

- 11 So Here’s My Question for You

Let’s talk about a plant you’ve probably never encountered.

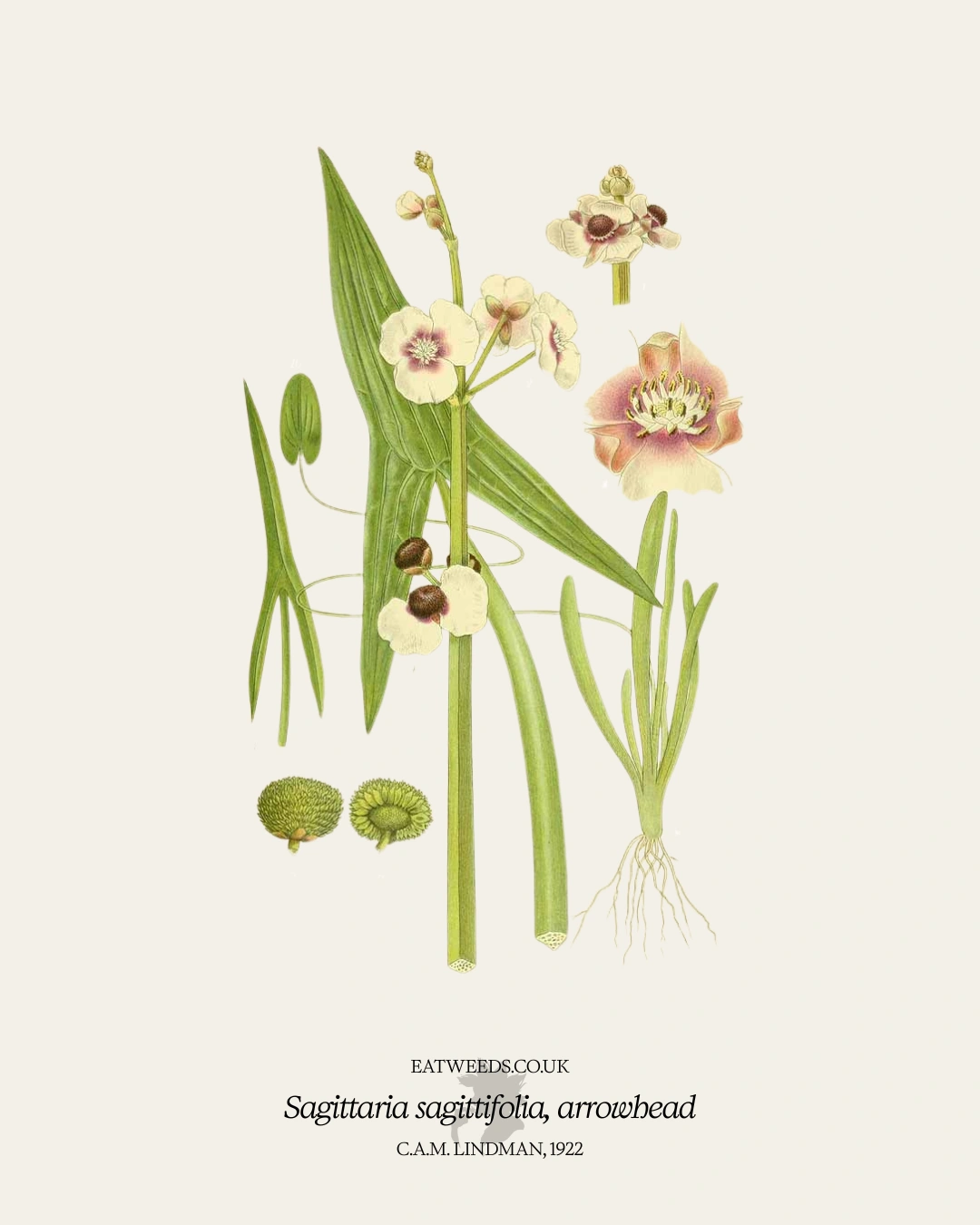

Sagittaria sagittifolia. Arrowhead. Swamp potato. Call it what you like.

For thousands of years, people across China and Southeast Asia have been eating this aquatic tuber. They’ve been thriving on it. Building entire food systems around it. Using it as both food and medicine.

And most of us in the West? We’ve never even heard of it. Yet we have our very own native variety.

That’s a problem. Because we’re missing out on something extraordinary.

Why You Should Care About This Plant

Picture this. You’re standing at the edge of a marsh. Arrow-shaped leaves poke up from the shallow water. Underground, beneath the mud, fat tubers are storing energy. Starch, protein, minerals, compounds that can strengthen your immune system.

This isn’t some exotic superfood fad. This is serious nutrition that’s sustained communities for millennia.

The tubers are packed with complex carbohydrates. Real, sustaining energy, not the blood sugar spike you get from simple starches. They contain significant protein for a vegetable. Essential minerals. Polysaccharides that modern science has confirmed can boost your immune function and scavenge free radicals.

Are you starting to see why this matters?

What Traditional Cultures Already Know

The Chinese have been cooking arrowhead tubers for centuries. Braising them with soy sauce. Adding them to winter soups. Frying them until they’re sweet and nutty.

In Traditional Chinese Medicine, arrowhead sits in that brilliant space where food and medicine blur together. It’s considered a tonic, something that builds vitality, supports resilience, strengthens the body over time.

Not a quick fix. Not a magic bullet. Just consistent, nourishing support for your health.

Throughout Southeast Asia, in places like Manipur, people eat both the tubers and the young shoots. They’ve worked out exactly when to harvest (late autumn for tubers, spring for shoots). They’ve mastered how to cook away the natural bitterness. They’ve integrated this plant into their food systems so completely that it’s just… normal.

What if we could learn from that?

The Science That Backs It Up

Look, I’m not asking you to take ancient wisdom on faith alone.

Modern researchers have been studying arrowhead. Pulling it apart. Testing its compounds. And you know what they’re finding?

The traditional uses hold up.

Studies by Gu and team (2020) confirm that polysaccharides extracted from arrowhead have powerful antioxidant properties. They can neutralise free radicals, those unstable molecules that age your cells and contribute to chronic disease.

More than that, these polysaccharides stimulate immune cell activity. They enhance your body’s natural defence mechanisms. This isn’t speculation. This is laboratory research validating what traditional practitioners observed through centuries of use.

Recent work has even explored selenium-modified arrowhead polysaccharides, showing enhanced antioxidant and potential anti-cancer properties (Feng et al., 2021). We’re talking about serious therapeutic potential here.

You don’t need to extract and isolate compounds to benefit from this plant. You can just… eat it.

Why It Works (And Why We’ve Ignored It)

The nutritional profile of arrowhead tubers is genuinely impressive.

High in carbohydrates? Yes. But complex carbs that provide sustained energy. Significant protein content, unusual for a starchy vegetable. Fibre. Minerals including phosphorus and potassium. All wrapped up in a package that grows wild in shallow water.

Think about that for a moment. This plant thrives in environments we often consider wasteland. Marshes. Pond edges. Places where conventional crops struggle. Yet it produces nutrient-dense food that can sustain entire communities.

Why aren’t we paying attention?

Partly, it’s cultural blindness. Western foraging traditions focus on terrestrial plants, berries from hedgerows, leaves from woodland edges. We’ve largely ignored aquatic vegetables, missing an entire category of wild foods that East Asian cultures have mastered.

Partly, it’s unfamiliarity. The tubers have a slight bitterness when raw. They require proper cooking; braising, long simmering, changing the water once during preparation. That’s more work than grabbing a potato from the supermarket.

But the reward? A distinctive, nutty sweetness. A firm yet yielding texture. Nutrition that rivals or exceeds common vegetables. And access to compounds that actively support your health.

How It’s Actually Used

Let me be clear about something. This isn’t theoretical.

Right now, today, you can walk into a Chinese grocery in most major cities and buy fresh arrowhead tubers. They’re sitting there in the vegetable section, waiting for people who know what to do with them.

The traditional preparation is straightforward. Peel the tubers. Braise them with soy sauce, sugar, and aromatics. The bitterness mellows. The natural sweetness emerges. You end up with something that’s halfway between a potato and a water chestnut, but more interesting than either.

Add them to winter soups. Fry them until caramelised. Steam the young shoots in spring like asparagus. Use different parts of the plant across different seasons.

This is practical, accessible food. Not Instagram-worthy superfood nonsense. Just solid nutrition from a plant that wants to grow in wet places.

The Modern Twist

Food scientists are now extracting arrowhead polysaccharides and exploring them as functional food additives. They’re developing methods to improve texture for processed products. They’re blending arrowhead starch with other aquatic vegetable starches to create novel food applications (Li-Cha, 2014).

Is that progress? Maybe. It certainly expands commercial possibilities.

But I’d argue we’re overcomplicating something beautifully simple. Why extract and isolate when you can just cook and eat the whole food? Why process it into additives when the tuber itself provides everything you need?

Sometimes the old ways are the best ways.

What We’re Really Talking About Here

This isn’t just about one plant. It’s about how we think about food, medicine, and the natural world.

East Asian food traditions don’t rigidly separate “food” from “medicine”. Nourishment itself is therapeutic. Medicinal plants are everyday foods. It’s an integrated approach that Western thought has largely abandoned in favour of rigid categories.

Arrowhead challenges those categories. It’s clearly food: starchy, sustaining, delicious when properly prepared.

It’s clearly medicinal: immune-supporting, antioxidant-rich, validated by modern research. It’s both. Neither. Something richer than either category alone.

And here’s what really matters: This integrated approach works. It’s sustained billions of people across thousands of years. It’s produced complex knowledge systems about how plants support human health. It’s created food traditions that modern science is only beginning to understand.

Maybe it’s time we paid attention.

The Questions You Should Be Asking

Why have we ignored an entire category of aquatic vegetables? What else are we missing by staying within our cultural comfort zones?

What knowledge exists in other traditions that could transform how we eat, how we forage, how we think about wild food?

Arrowhead is just one example. One plant among thousands that other cultures know intimately whilst we remain ignorant.

That’s not a small thing. That’s a massive blind spot in our relationship with the natural world.

What You Can Actually Do

If this resonates with you, here’s what I suggest.

First, find a Chinese grocery. Look for arrowhead tubers in autumn and winter. Buy some. Take them home. Try the traditional braising method, soy sauce, sugar, aromatics, long slow cooking.

See what you think. See if that nutty sweetness appeals to you. See if your body responds to regular consumption of something that’s sustained communities for millennia.

Second, expand your definition of foraging. If you’ve got access to shallow freshwater environments, ponds, marshes, slow streams, learn to identify arrowhead by its distinctive arrow-shaped leaves. Understand when and how to harvest sustainably. Add aquatic plants to your repertoire.

Third, get curious about other food traditions. What do they know that you don’t? What plants do they value that you’ve overlooked? What preparation methods have they perfected through generations of use?

This isn’t about cultural appropriation. It’s about learning. Respecting. Expanding your knowledge and your diet in ways that honour traditional wisdom.

The Bigger Picture

Arrowhead tubers won’t change your life overnight. They’re not a miracle cure. They’re not going to make you suddenly enlightened or transform your health in a week.

What they offer is something more valuable. Solid nutrition from a renewable source. Access to compounds that support long-term health. Connection to knowledge systems that predate modern science but increasingly align with it.

And maybe most importantly, they offer a challenge to your assumptions. About what counts as food. About where nutrition comes from. About whose knowledge matters.

That’s worth more than any superfood trend.

So Here’s My Question for You

Are you willing to step outside your comfort zone? To learn from traditions that aren’t your own? To try a plant you’ve never encountered and see what it might offer?

Because here’s the truth. The natural world is full of plants like arrowhead, nutritious, accessible, used by some cultures but ignored by others.

Each one represents an opportunity to expand your knowledge, diversify your diet, and build resilience.

The choice is yours. Stay comfortable with what you know. Or push into new territory and see what you discover.

I know which one I’m choosing.

References

Ahmed, M., Ji, M., Sikandar, A., Iram, A., Qin, P., Zhu, H., Javeed, A., Shafi, J., Iqbal, Z., Iqbal, M., & Sun, Z. (2019). Phytochemical Analysis, Biochemical and Mineral Composition and GC-MS Profiling of Methanolic Extract of Chinese Arrowhead Sagittaria trifolia L. from Northeast China. Molecules, 24(17), 3025.

Feng, Y., Qiu, Y., Duan, Y., He, Y., Xiang, H., Sun, W., Zhang, H., & Ma, H. (2021). Characterization, antioxidant, antineoplastic and immune activities of selenium modified Sagittaria sagittifolia L. polysaccharides. Food Research International, 153, 110913.

Gu, J., Zhang, H., Wen, C., Zhang, J., He, Y., Ma, H., & Duan, Y. (2020). Purification, characterization, antioxidant and immunological activity of polysaccharide from Sagittaria sagittifolia L. Food Research International, 136, 109345.

Gu, J., Zhang, H., Yao, H., Zhou, J., Duan, Y., & Ma, H. (2020). Comparison of characterization, antioxidant and immunological activities of three polysaccharides from Sagittaria sagittifolia L. Carbohydrate Polymers, 235, 115939.

Li-Cha, Z. (2014). Gel Characteristics of Starch Blends from Sagittaria sagittifolia, Eleocharis dulcis and Trapa natans. Modern Food Science and Technology.

Sun, Y., Liu, Y., Li, J., & Yan, S. (2023). Acetic Acid Immersion Alleviates the Softening of Cooked Sagittaria sagittifolia L. Slices by Affecting Cell Wall Polysaccharides. Foods, 12(3), 506.

Robin Harford

Robin Harford