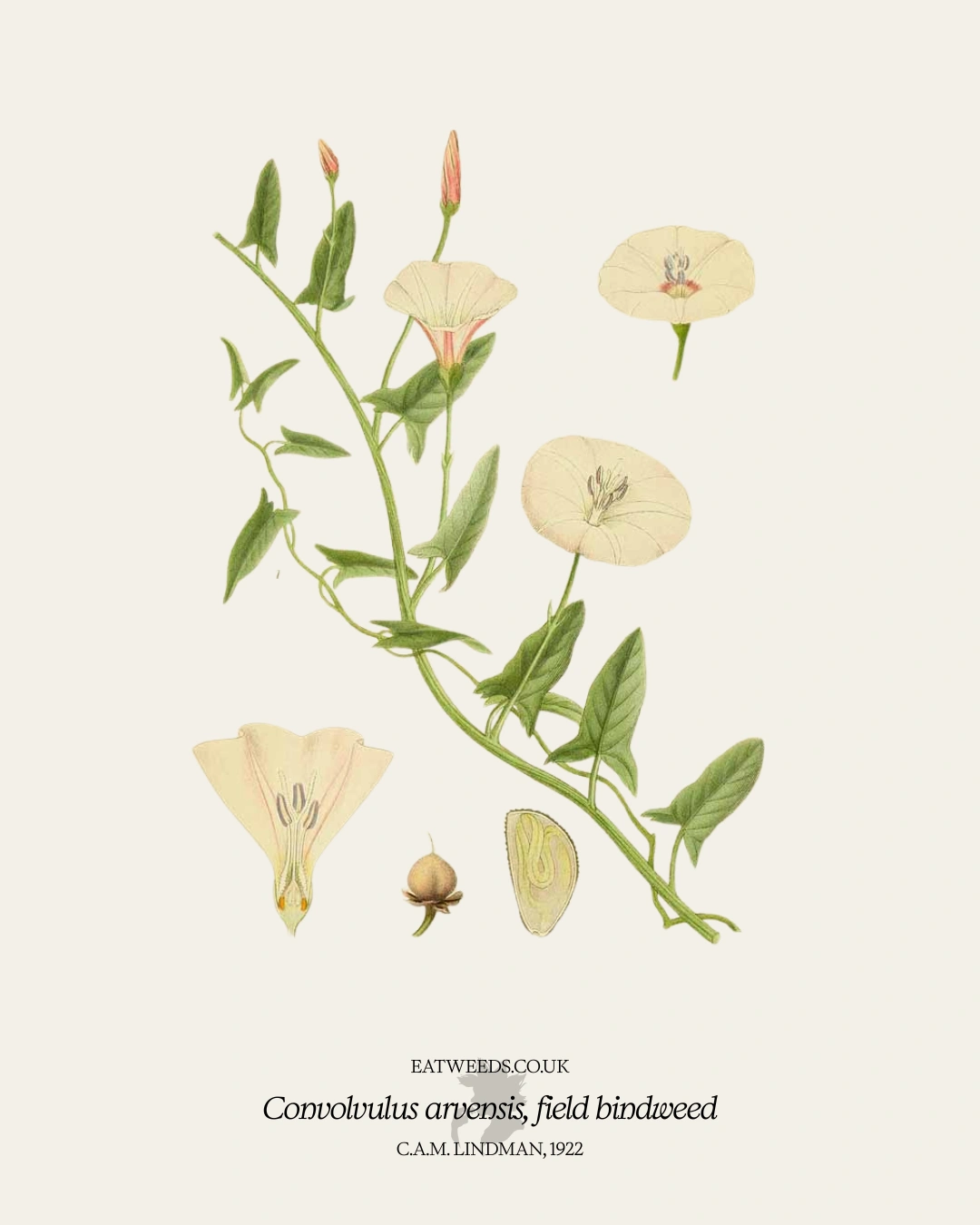

Scientific name

Convolvulus arvensis

Family

Convolvulaceae

Photo identification

Reliable resources for accurate botanical photo identification of field bindweed.

Habitat and distribution

Cultivated land, dunes, hedgerows, roadsides, short turf, wasteland.

Entomology

Flowers

May, July, August, and September

Safety note

WARNING: Very experimental; tread cautiously.

Just because a plant was used as food in the past does not mean it is safe to eat. Borage and comfrey are classic examples of this. When you see a warning on these plant profiles like this, it is for a reason, consume at your own risk.

Bindweed contains several alkaloids, including pseudotropine and lesser amounts of tropine, tropinone, and meso-cuscohygrine.

Recently a scientist from a French university contacted me. She wrote:

“Here is an article about the distribution of ergot-alkaloids in different plant parts of several Ipomoea species, comparing untreated with fungicide-treated seeds to try to figure out how much was due to the plant (answer = probably some) and how much to the fungus (answer = more).

Admittedly I have found nothing on Convolvulus, but I suspect this means that nobody has looked, not that there is none.

The toxicity of Morning Glories was (in part at least) due to ergot-like producing micro-organisms that grow endophytically.

Because of this, since infection rates with these microbes can vary over time and space, but that some are very very toxic and disturbing, it may be best to avoid morning glories entirely.”

Edible parts

Rhizomes, young shoots, young rosettes, young leaves, seeds.

Edible uses

In Croatia, the leaves are boiled and eaten as a vegetable.

In China, tender young rhizomes with a few young leaves are gathered from sorghum fields in early spring, mixed with cracked wheat and ground beans and made into a thin gruel. They are used in very small amounts as too much will cause diarrhoea.

In Spain, in the regions of South Eastern Albacete and South Central Jaen, the flowers are sucked for their honey-like nectar. They are not eaten. In Palencia, the leaves are boiled before being added to salad.

In Turkey, they cook the leaves in with other vegetables.

In Ladakh, the leaves are eaten raw as well as cooked. The seeds are boiled in onion and tomato and then fried in oil before being eaten. Tender young leaves and shoots are boiled and washed extremely well with water before being mixed with curd in a dish called tangthour.

In Poland, at the end of the 19th century, young shoots were gathered and boiled, then fried with butter, cream, flour or eggs.

Links

- Edible and medicinal wild plants of Britain and Ireland

- Forage in spring

- Forage in summer

- Forage in autumn

References

Couplan, F. & Coppens, Y. (2009) Le Régal végétal: plantes sauvages comestibles. Paris: Sang de la Terre.

Hu, S. (2005) Food plants of China. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

Jain, S. K. (2016) Indian ethnobotany emerging trends. India: Scientific Publishers.

Kizilarslan, Ç. (2012) An ethnobotanical study of the useful and edible plants of Izmit. Marmara Pharmaceutical Journal. [Online] 3 (16), 194–200.

Luczaj, L. et al. (2013) Wild food plants used in the villages of the lake Vrana nature park (northern Dalmatia, Croatia). Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae. 82 (4).

Muthaiah, P. et al. (2010) Phytofoods of Nubra valley, Ladakh – The cold desert. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge. 9303–308.

Pascual, J. & Herrero, B. (2017) Wild food plants gathered in the upper Pisuerga river basin, Palencia, Spain. Botany Letters. [Online] 1641–10.

Tardío, J. et al. (2006) Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants in Spain. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. [Online] 152 (1), 27–71.

Robin Harford

Robin Harford